Four Boundaries of Mahābhārat

An Analysis of the Critical Edition

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1 | Beyond the central war narrative

Most of us have pieced together the many stories of the Mahābhārat [Mhb] that we have heard over time to create a more comprehensive narrative. However, while we accumulate the middle portion of the story throughout our lives, we must understand where, how, and why the Mhb starts and finishes the way it does.

Understanding the boundaries of the Mhb, its beginnings and endings reveal unique aspects of the epic, how we should interpret the story and what we can learn from it.

1.2 | Narrative tradition vs earliest manuscript

However, when we say "Mahābhārat", which one do we mean?

Looking past the many retellings and adaptations, the text supposedly composed by Vyās has many variations, making the discussion about its boundaries subjective. So, for this essay, we shall stick to the BORI or Critical Edition [CE] of the Mhb1 as we can trace a clear start and finish to the story in the text. Nevertheless, we first need to understand how we have received the epic in its current form.

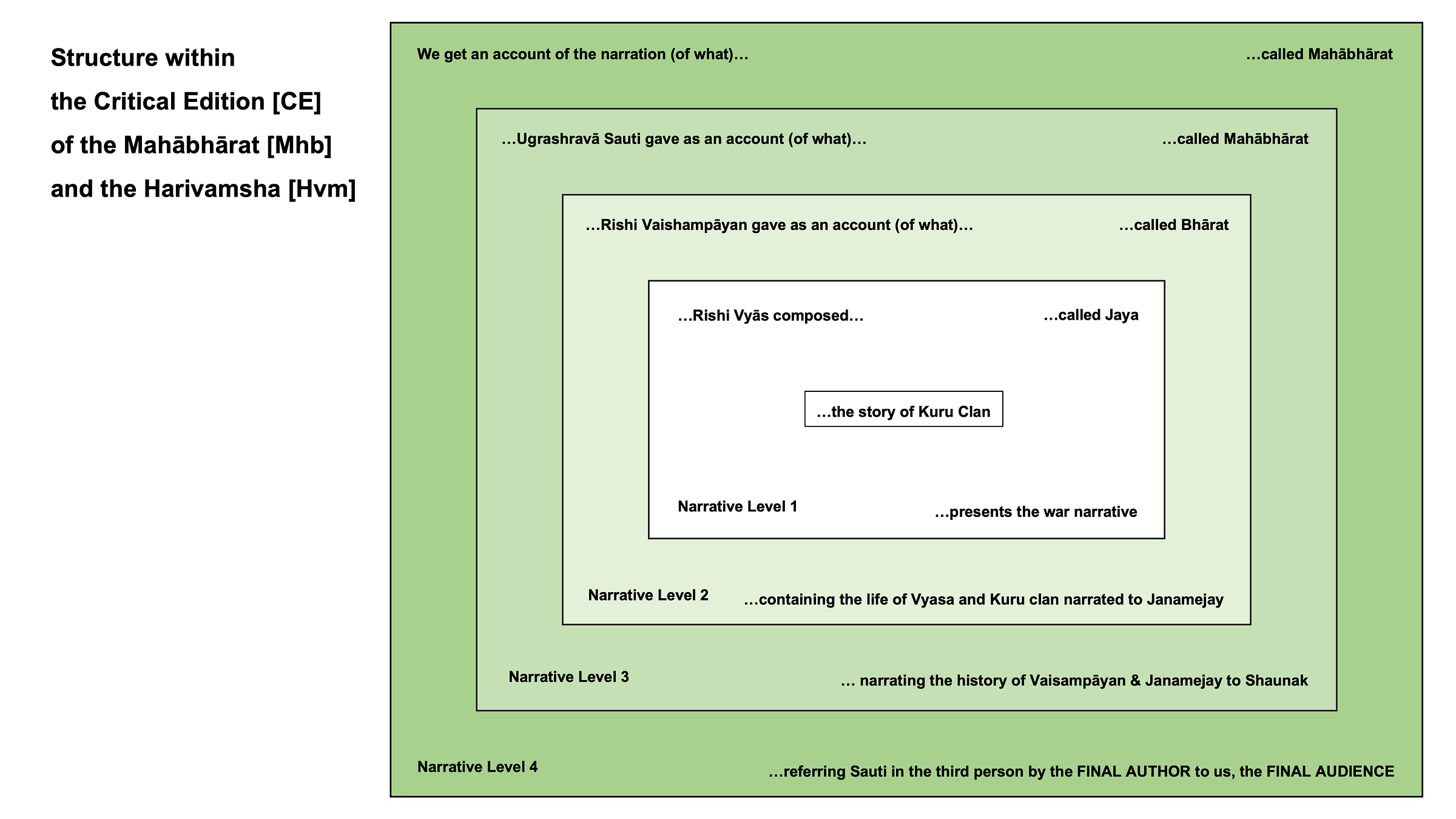

We must unpack two aspects of Mhb CE – its structure and classification.

2. MAHĀBHĀRAT’S STRUCTURE

2.1 | The narrative layers of the epic

Is Mhb. a single story being linearly told to us as it is happening? Not exactly.

Explaining the structure in epic helps to see the various frames in terms of narrative layers[Note 1]. There are four narrative layers of storytelling in the Mhb CE:

In Narrative Layer 1

[L1], Sanjay reports the main war to King Dhitrāshtr, and Vyās composes an epic around it [as Jaya]. This layer also contains voices from others narrating voices before and after the war.

In Narrative Layer 2

[L2], we have Vaishampāyan's retelling of Vyās' composition and Vyās' history to Janmejay at the Sarpa Satra or snake sacrifice [as Bharat].

In Narrative Layer 3

[L3], we are witnessing Ugrashravās Sauti's retelling of Vaishampāyan's account of Shaunak and the sages during the 12-year sacrifice yagna at Naimisharanya or Naimisha Forest [as Mahābhārat].

Finally, in Narrative Layer 4

[L4], the story takes the final form where Ugrashravās’ account is being narrated to…us, the FINAL AUDIENCE [as Mahābhārat], by an unnamed voice whom we can consider the FINAL AUTHOR[Note 2].

Note 1:

Many scholars have discussed the "inner frame" [what we here are calling Narrative Layer 2] and the "outer frame" [what we here are calling Narrative Layer 3], as most of the story in the epic is told primarily through these two frames2[citation 2]. We have also named the other two layers because they help us think and talk about the events happening in those.

Note 2:

Many scholars have referred to this as 'The narrator' or 'anonymous bard' and other names. However, it is better to use the term FINAL AUTHOR as it shifts the focus on the action of this figure whose composition is the only one we can access. So, credit where credit is due. Besides, it is better than the alternatives that seem fixated on the lack of identity. Furthermore, there is some poetic justice in calling the FINAL AUTHOR and ourselves the FINAL AUDIENCE.

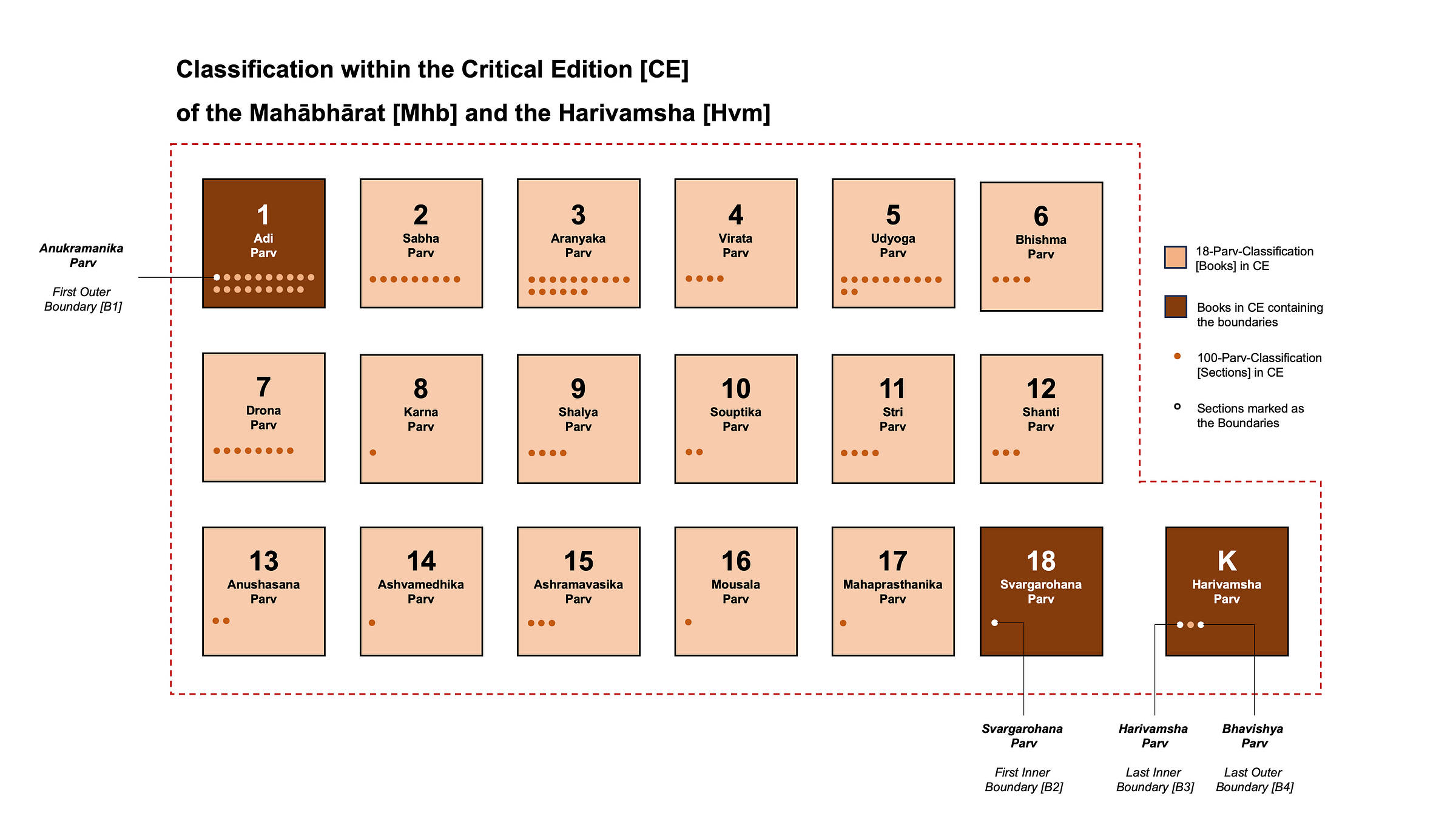

3. MAHĀBHĀRAT’S CLASSIFICATION

3.1 | Relationship of Itihās with its khilā

Mhb CE comprises 18 books and 95 sections, while Harivamsha [Hvm] CE is one book with three sections[Note 3]. The relationship between the Mahābhārat and the Harivamsha is similar to one between the main text and its appendix [khila]. Like Mahābhārat, Harivamsha is also multi-genre in Indic literation and is attributed to Vyās. However, evidence shows it is a later addition.3

While the main text speaks about the ancestry and conflict of the Kuru clan, with Krishn playing a pivotal role, the appendix speaks about the ancestry of Krishn and his divine deeds before the events of Mahābhārat. ‘It is not the individual works but the conversation between them that speaks to this deeper understanding’.4

Note 3:

Mhb CE's table of contents showcases 18-Parv-classification [what we will refer to as Books] and 100-Parv-classification [what I am referring to as Sections]. It is important to note that Mhb CE only kept 98 sections of 100 that were supposed to be there.

Hvm. on the other hand, is not treated like another book - as the 18-Parv-classification ends with Svargarohan Parv - but its three sections are listed and counted within the 98 mentioned.

To understand this conversation between the main text and the appendix, we must examine the boundaries of the epic that show the two ends and two beginnings.

Essentially, there are four boundaries across Mhb CE:

The first outer boundary

[B1], i.e. The beginning in Section 1 ofMhb, Anukramanika Parv5

The first inner boundary

[B2], i.e. The ending in Section 95 ofMhb, Svargarohan Parv6

The last inner boundary

[B3], i.e. The beginning of Section 1 ofHvm, Harivamsa Parv7

The last outer boundary

[B4], i.e. The ending in Section 3 ofHvm, Bhavishya Parv8

Let us start with the inner boundaries, which are both an ending and a beginning.

4. FIRST INNER BOUNDARY [B2]

4.1 | Overview of Mahābhārat, Section 95 - Svargarohan Parv

The Svargarohan Parv is the last section of Book 18 of the Mhb CE [also named Svargarohan Parv]. It is titled so as it has the climactic post-war story of the Pandavs' journey to the Himalayas to ascend to heaven. Interestingly, it concludes with verses extolling the sacredness of the epic that is contrasted with Vyās' expression of deep sorrow and frustration.

4.2 | Epic's self-importance

After the story of Pandavs finishes, we hear Ugrashravās Sauti repeating the oft-quoted famous verse [first time by Vaishampayan in Chapter 56 - Adi Vamshavataran Parv9:

Bull among Bharatas, whatever is here, on law, on profit, on pleasure and salvation, that is found elsewhere, But what is not here is nowhere else.

— The Mahābharata, Vol 10 [Bibek Debroy], pg 682 [Quote 1]

Following this verse is a reminder verse [first time by Sauti in Chapter 1 - Anukramanika Parva10 about how Mbh was composed, transmitted and consumed by different sets of audiences:

For the sake of ensuring dharma, the lord Krishna Dvaipayana, who will not return, composed a summary known as Bharata, and it took him three years. Narada recited it to the gods, Asita-Devala to the ancestors, Shuka to rakshasa and yakshas and Vaishampayan to mortals.

— The Mahābharata, Vol 10 [Bibek Debroy], pg 682 [Quote 2]

More verses repeatedly praise the text from the voice of Ugrashravās Sauti directly to Shaunak at L3. It is probably an understatement to say how ‘the text took its role as ithāsa very seriously. Thus, it promises to have fulfilled its role most comprehensively.’11

4.3 | Vyās's Lament

The repeated harping of its genre-defying importance12 and commemorating its ascribed author is bound to make Mbh. CE seems arrogant. It does not help that the text is so sure about its potent powers that it proclaims how even a partial reading can have the desired effect.

However, interestingly, this reverence of the story and the author is sharply contrasted - or more accurately, cut in - with the lamentation of Vyās:

Thousands of mothers and fathers and hundreds of sons and wives arrive in this world and then depart elsewhere. There are thousands of reasons for joy and hundreds of reasons for fear. From one day to another, they afflict those who are stupid, but not those who are learned. I am without pleasure and have raised my arms, but no one is listening to me. If dharma and kama result from artha, why should one not pursue artha?

— The Mahābharata, Vol 10 [Bibek Debroy], pg 682 [Quote 3]

At a surface level, he is wailing about the loss of countless lives, the destruction of families, and the moral decay that accompanies the conflict. Vyas' lament stems from the realisation that his descendants played a significant role in perpetuating the war, further adding to his sense of guilt and remorse.

On the other hand, it is almost suggestive that ‘the eternal truth doesn't deserve to be handed out as a freebie; it needs to be realised by sustained tapas’13. There is difficulty in accessing and processing any truth — let alone one so complex and steeped in culture's narrative tradition.

Alternatively, looking at the way Mahābhārat's popularity grew over time, this verse can hint at the author's frustration with the future - our present: A present where the evolving and contemporary interpretations of the epic will outlive his original intentions, which is at the risk of being lost within the text.

What is fascinating is that this annoyance is not only displayed by Vyās as a narrator in L2 but by Janamejaya in L2 and Shaunak in L3 as audiences in the next boundary of Mhb CE.

5. LAST INNER BOUNDARY [B3]

5.1 | Overview of Harivamsa, Section 1 - Harivamsa Parv

Since Hvm CE is structured similarly to Mbh CE, in terms of the narrative layers, its beginning continues developing the dynamics of the author-audience relationship to tell the story.

5.2 | Audience's dissatisfaction with the narration

The section begins at L3, where Shaunak thanks Sauti for all the stories told and then points out:

O Souti! You have recounted the extremely great account of those born from the Bharata lineage, all the kings, the gods, the danavas, the serpents, the rakshasas, the daityas, the siddas, the guhyakas, their extraoridinary acts of valour, the supreme and wonderful accounts of their births and the determinations of dharma. In gentle words, you have spoken about these sacred and ancient accounts. Our minds and ears have become happy and delighted and are full of amrita.

O Lomaharshana's son! You have also spoken to us about the birth of those from the Kuru lineage. However, you have not spoken about the Vrishinis and the Andhakas. Tell us about them.

— Harivamsha [Bibek Debroy], pg 2 [Quote 4]

It is peculiar that in framing Shaunak's request as “you have not spoken about…”, a tone of dissatisfaction is hinted with a sense of inquiry.

Cleverly, Shaunak summarises what he has heard so far —a narrative technique used to recap where we are in the epic—almost as if this was a memory device used by bards in oral tradition.

Also, Shaunak, as an audience member, to Sauti's authorial voice in L3, shows the unique characteristics of pushing to co-create the narrative by asking pointed questions.

What is even more peculiar is that Ugrashravās does not directly jump into the story but says:

Janamajaya asked Vyasa's intelligent disciple about this. Following this, I will tell you the truth about the lineage of the Vrishnis, from the beginning. After having heard the entire history about the Bharata lineage, the immensely wise Bharata Janamejaya spoke to Vaishampayana…

— Harivamsha [Bibek Debroy], pg 2-3 [Quote 5]

It is almost like Sauti was waiting for this. He is not just answering the question in prose or chronology but recounting the narrative as Janamejay asked Vaishampāyan.

Going into L2 we now hear Janamejay's voice:

"The account of the Mahabharata has many meanings and is extensive in its compassion.

…

O brahmana! You have told me about it in detail and I heard it. You have spoken about many brave ones, bulls among men, and the names and deeds of the maharatha Vrishnis and Andhakas.

…

O supreme among brahmanas! You have also spoken about their deeds. O lord! However, you have only spoken about this briefly and not in detail. I am not satisfied with what you have already recounted.

…

It is my view that the Vrishnis and the Pandavas were related. You know about their lineages and were a direct witness.

…

O store of austerities! Speak about their lineage in detail. I wish to know about who was born in whose lineage. What is the wonderful story of their being created earlier, by Prajapati?"

— Harivamsha [Bibek Debroy], pg 3 [Quote 6]

Janamejay is not only more candid but also more pampering in his requests. His statement, "I am not satisfied with what you have already recounted", is direct, whose sharpness gets blunted by the praises before. Interestingly, he ends his speech with a loaded question primed for an elaborate narration for an answer.

5.3 | Authors pleased with the peculiarity

Through Janamejay's voice [in L2], Souti [in L3] acknowledges Shaunak's dissatisfaction with the incomplete retelling. In choosing to answer it by telling about the conversation in L2, Souti is taking the narrative to where it needs to go.

This trick becomes even more apparent when we see Vaishampayan's response to Janamejay's accusatory question:

"O king! Listen to the sacred and divine account, one that is destructive of all sins. I will tell you about these wonderful and diverse accounts, honoured in the sacred texts. …O son! If a person sustains this ceaselessly listens to it, he manages to uphold his own lineage and obtains greatness in the world of heaven…"

— Harivamsha [Bibek Debroy], pg 3 [Quote 7]

Vaishampāyan does not start narrating the story directly but first starts with the benefits of hearing it. One can almost feel the gleefulness in his tone in the verses. A natural reaction expected after speaking so long to the way Janamejay's comment about 'not being satisfied' should have been an annoyance, but Vaishampāyan strangely does not seem to be offended or defensive in his response. A pleased response meets the peculiarity of the questions. It is almost like the conversation is unfolding how it is supposed to…

Let us now explore outer boundaries by first going back to the beginning.

6. FIRST OUTER BOUNDARY [B1]

6.1 | Overview of Mahābhārat, 1st book - Anukramanika Parv

The Anukramanika Parv, Section 1 of the Mahābhārat, is an introduction and index to the epic. It consists of Ugrashravās narrating the Mahābhārat to a gathering of sages led by Shaunak in L3. Ugrashravās shares that he learned the epic from Vaishampāyan, a disciple of Vyās. In L2, Vaishampāyan recounts the story to Janamejay, a descendant of the Pandavs, who desires to hear the complete story of the Mahābhārat. Thus, the Anukramanika Parv sets the epic tale's stage and establishes the narrative framework of the subsequent books.

6.2 | Voice of the FINAL AUTHOR

Noticeably, the starting verses are an invocation given as instruction by the FINAL AUTHOR, present in L4. The invocation is about the ritualistic prerequisites for reciting the story [Jaya, about to be told].

It is rare to hear this authorial voice. It is even more mysterious to know why it even exists. Moreover, why does this voice narrate the L3 and not choose to describe the L2 or L1 directly?

Many scholars have asked - and dodged - this question14:

Who is speaking here? It is a voice heard only occasionally in the poem, although in a sense, it is the only voice we ever hear. [Author Adam] Bowles calls it "the implicit bedrock upon which all other frames are ultimately founded". [Author Alf] Hiltebeitel calls it "the authorial frame," "an outermost frame that gives the author his openings into the text, and both reveals and conceals its ontology". It was hardly noticed by earlier critics, probably because the narratives other two frames are so highly developed by comparison…

— Beginning the Mahābhārata [2011] James W. Earl, pg 12 [Quote 8]

It is hard to answer the question about the FINAL AUTHOR without going into speculation [and conspiracy theories], but its effect on the epic is noticeable.

At one level, the lack of acknowledgement of the narrator of the outermost frame [L4] is a way to enforce the nature of Itihās as a mode of communication for retelling. At another level, the FINAL AUTHOR's lack of identity allows the figure of Vyās - the original ascribed author - to seize that role and be considered the epic's sole author.

In many ways, even the need to assign an identity to this author reflects the rigidity in our concepts about literary work, author, and ownership - something Mhb—challenges by its storytelling. Despite having an ascribed author, the epic, with its story-within-a-story framing, reinforces the notion that Itihāsic tradition transcends beyond an individual's contribution.

This collective nature of storytelling embodied within the epic creates a space for continuous retelling and reimagining, propelling its popularity through generations.

6.3 | Audiences' pre-existing awareness of the epic

Down in L3, when Ugrashravās Sauti meets the sages in Namishāranya forest, there is another strange phenomenon that can be observed, especially in their initial conversation:

Souti said: …

What shall I say? Shall I state the sacred stories of the Puranas, the source of dharma and artha? Shall I speak of the history of kings among men an sages and great souls?

The sages replied:

Tell us that ancient story that was told by the supreme sage Dvaipayan, that which was worshipped by the gods and the brahmarshis when they heard it — and that which is full of wonderful words and divisions and is the supreme of narratives, with subtle meanings and logic, adorned with the essence of the Vedas. That sacred history of the Bharatas is beautiful in language and meaning, and includes all other works. All the shastras add to it and that sacred composition of great Vyasa has been added to the four Vedas. We wish to hear that holy collection, that drives away fear of sin, just as it was recited at King Janamejaya's sacrifice by Vaishampayana'

Souti said:

I bow to the orignal being Ishana, adored by all and to whom all offerings are made….

… I will describe to you the holy thoughts of that great sage who is venerated in the entire world, Vyasa, the performer of wonderful deeds. Some poets have already sung the story before. Other poets are teaching this history now. In the future, still others will certainly do this on earth…

— The Mahābharata, Vol 1 [Bibek Debroy], pg 3 [Quote 9]

The interaction brings out a few mysteries. Audiences in L3 are aware of the epic - but whether they are only mindful of the existence of such an Epic or even of its content – is not known. Their specific description of its effect would suggest that they may have known the story and are just looking to hear it again [like children asking for their favourite bedtime story].

Moreover, what motivates them to re-hear the epic right now if they are already semi-aware of the story? Is it necessitated by a need for entertainment – a leisure pass time between the snack sacrifice sessions? Or is it driven by curiosity to fill gaps in their knowledge and transform themselves? Perhaps it is for our benefit as the FINAL AUDIENCE - to get us to be part of this ongoing conversation.

6.4 | Multiplicity of engagement and entry

Upon being asked to tell the story, Sauti does not just begin reciting it but further builds the suspense by suggesting multiple entry points and ways to engage with the story:

Some read Bharata from the story of Manu, others from the story of Astika, still others from the story of Uparichara. Some brahmanas read the entire text. Learned men display their knowledge of the samhitas by commenting on this collection. Some are skilled in explaining it, others in remembering it.

— The Mahābharata, Vol 1 [Bibek Debroy], pg 5 [Quote 10]

It is almost like Sauti presents these choices to test the sages' patience. Moreover, in L4, the FINAL AUTHOR, through Sauti, is pushing us, too, compassionately goading us to stay the course or skip ahead if we want [at our own risk of understanding] and reminding us that a partial reading of the epic is not only permissible but just as poignant.

There is, however, some scepticism expressed in academic readings regarding this paradox:

That is fair warning that a sequential first reading of the poem will be a vastly diminished reading, because an awareness of the whole is assumed from the very start. This assumption is apparent even in the poem's frame story: the poem is represented as being presented to an audience of forest hermits who seem already to have heard it before.

— Beginning the Mahābhārata [2011] James W. Earl, pg 4-5 [Quote 11]

The choice may be up to us on how we want to heed Ugrashravās' suggestion. One solace in his commentary about the different methods of interacting with the story employed by other people does reflect that — at least at the time of L3 — there were already many retellings of the epic floating. Furthermore, we know Vyās had delegated the epic’s narration when he allowed his disciple Vaishampāyan to recite it and even teach it to others who must have found their known audiences.

We only hear this particular retelling because the FINAL AUTHOR chose it to tell it…or because this is what survived.

7. LAST OUTER BOUNDARY [B4]

7.1 | Overview of Harivamsa, 3rd book - Bhavishya Parv

The Bhavishya Parv is the third book of the Harivamsa and serves as the conclusion of the Harivamsa Parv. It contains stories and prophecies about the future [its name, "Bhavishya", means "future"]. In it, Vyās is again the central figure who narrates the events and prophecies to his disciple Vaishampāyan. This section also predicts what is to come in the future.

7.2 | Last voice heard in the epic

In Mhb CE and Hvm CE, the epic narratives start and end with narrative layer 4, where an unknown voice, referred to as the FINAL AUTHOR, addresses the final Audience. This enigmatic narrator, who remains unnamed, is the conduit between the timeless stories of the past and the present-day readers.

Through this FINAL AUTHOR, the epic comes alive, bridging the gap between ancient events and the contemporary world. These are the last verses in the section:

...You must remember that this account was recited in an assembly of brahmanas. If you remember this, patience will again be generated in you and will roam around the world, happy. The great-souled rishi composed this account about the conduct of those who were brave in their deeds. I have recounted it, briefly and in detail. What else do you desire that I should speak about?

— Harivamsha [Bibek Debroy], pg 441 [Quote 12]

By reminding us that the account of the epic was recited in an assembly of Brahmanas [that happens at L3], we know this is not Ugrashravas Sauti's voice.

Secondly, by referring to Vyās as 'The great-souled rishi [who] composed this account…' and then using a first-person voice in the following sentence ["I have recounted it…"], we can also deduce that this is not Vyās’ voice.

This leaves us with the fact that this is the FINAL AUTHOR's voice speaking to us, the FINAL AUDIENCE, at L4.

7.3 | The Parting Question

However, it is his words that are worth noting. The FINAL AUTHOR poses a question to us as the FINAL AUDIENCE, which acts as a request and an invitation to reflect on our desires and interests within the narrative. Unlike the first verses at the beginning of the epic, which were instructions provided, the last verse at the end of the epic is to be answered by us, the FINAL AUDIENCE.

With just that question, the FINAL AUTHOR is prompting us to consider what more we seek from the story and what we hope to gain from further exploration.

8. CONCLUSION

Through the lens of these four boundaries - and across the epic - there is a sense of interaction and co-creation between the authorial storytellers and the listening audiences. What is thus evident in Mhb CE is that the epic ‘often unfold[s] through multiple narrative voices that diverge from and question one another’, making it an ‘interrogative mode of storytelling’15

Thus, the epic's endings and beginnings set the narrative structure and classification, emphasising the communal nature of storytelling and the shared responsibility of preserving and transmitting cultural narratives. These boundaries serve as reminders of the enduring power of oral tradition and the dynamic relationship between the authors, the audience, and the epic itself.

At the heart of it all, the purpose of the epic is 'the telling of the story itself'. Moreover, therein lies its enigmatic appeal because the Mahābhārat as a story ‘inherently invite more Mahābhārats’16 [citation 16] to be created and consumed.

All that is needed is asking a question and participating in the conversation.

This essay was originally published in MythKatha Vol 3 (pages 15-24), a mythology magazine by Mythopia. It has been slightly modified here for formatting and ease of reading.

9. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

I want to thank the co-founders of Mythopia, Radhika Radia and Neelkanth Mehta, for the opportunity to contribute to their magazine volume.

Along with the resources cited, I want to thank all the authors, researchers and creators (like Ami Ganatra, Kanad Sinha, Tanuja Ajotikar, Prasad Bhide, Nityānanda Miśra, Vishal Chaurasia—to name a few) whose shoulders—and body of literature—I could stand on for creating this essay and making a meaningful contribution to the conversation.

Also, a special shout-out to my wife, Rohina Thapar, who has supported me through the entire process - from pushing me to take this up and pulling me out of my research hole to polishing the final draft.

And lastly, I am very grateful to my family for their unwavering belief in me and support in whatever I do.

This essay is a labour of love. It has helped me articulate and coalesce many of my perspectives on not just the epic of Mahābhārat but also on mythology and storytelling itself. It has also made me realise the value and efforts that go into creating content.

So, this is the beginning, with more to come….

We refer to Bibek Debroy’s Mahabharata 10 Volume English unabridged translation of Critical Edition whenever Mbh. CE or Hvm. CE is mentioned, we. A disclaimer: While Debroy’s books are a massive help, it is not without their limitations & controversies amongst many Indic scholars, so one needs to remember that, at best, things may be lost in translation or, worse, there are mistranslations.

Beginning the Mahābhārata [2011], James W. Earl, pg x

The origin of this appendix is not precisely known, but it is apparent that it was a part of the Mahabharata by the 1st century CE because "the Buddhist philosopher and poet Ashvaghosha quotes a couple of verses, attributing them to the Mahabharata, which are now only found in the Harivamsa", See Datta 1858

Many Mahābhāratas, pg 13-14, [Nell Shapiro Hawley & Sohini Sarah Pillai]

The Mahābharata, Vol 1, Anukramanika Parva, pg 1-3, [Bibek Debroy]

The Mahābharata, Vol 10, Svargarohana Parva, pg 682-683, [Bibek Debroy]

Harivamsa, Harivamsa Parva, pg 2, [Bibek Debroy]

Harivamsa, Bhavishya Parva, pg 440-441, [Bibek Debroy]

The Mahābharata, Vol 1, Adi Vamshavataran Parva, pg 151, [Bibek Debroy]

The Mahābharata, Vol 1, Anukramanika Parva, pg 6, [Bibek Debroy]

From Dāsarājña to Kuruksetra, pg 10 [Kanad Sinha]

Author Alf Hiltebeitel points out that the Mahābhārata refers to itself using several different genre designations: ithāsa [history], ākhyāna [narrative], purāna [an extended myth narrative], kathā [story], carita [biography], śāstra [treatise], samhitā [collection], upākhyāna [tale], Upaniṣad, and Veda. See “Not without Subtales: Telling laws and Truths in the Sanskrit Epics” in Argument and Design: The Unity of the Mahābhārata.

Evolution of Mahabharata and Other Writings on the Epic [S.R.Ramaswamy], pg 31

Beginning the Mahābhārata, pg 12, [James W. Earl]

Divine Yet Human Epics: Reflections of Poetic Rulers from Ancient Greece and India, pg 174, Shubha Pathak

Many Mahābhāratas, pg 3, [Nell Shapiro Hawley & Sohini Sarah Pillai]

Very nicely and lucidly explained. The graphics make it easier to understand these different layers of Mahabharata. Looking forward to more.